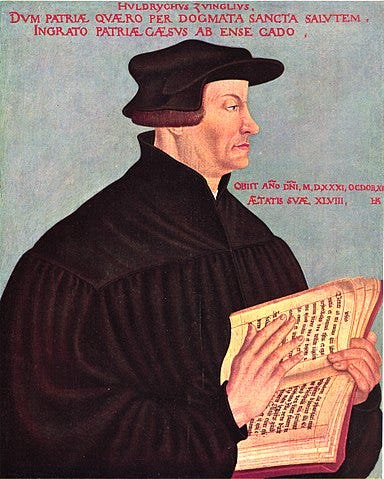

Ulrich Zwingli 1484 - 1531 Public Domain

Early Life

Ulrich (also spelled Huldrych) Zwingli was born in Wildhaus in Switzerland on January 1, 1484. His parents were farmer; Ulrich was the third of eleven children. His early schooling was from his uncle Bartholomew, a cleric. He went to the city of Basel for the next step in his education. In three years, he studied many subjects including Latin. Then he moved to Bern to study. While there, it is possible he became a novice in the Catholic Dominican religious order.

Ulrich left Bern, due to the disapproval of both his father and uncle. Entering the University of Vienna in 1498, it is unclear if he was expelled. There until 1502, he then entered the University of Basel, where he earned the Master of Arts Degree in 1506. Moving to the city of Constance, he was ordained as a priest in September 1506. The new priest was assigned to the city of Glarus in eastern Switzerland, staying for ten years.

At that time, the Swiss Confederation was involved with the French, the Papal States and the powerful Habsburgs. Zwingli became involved in politics and allied himself with the Pope. The Pope of that era, Julius II, awarded a yearly pension to the young priest. Zwingli became a military chaplain and was present at several battles in Italy. Up to this time, the Swiss infantry often acted as mercenaries and were highly successful and feared throughout Europe. Yet, at the Battle of Marignano, French and German landsknechts decisively defeated the Swiss. Many Swiss in and around Glarus shifted their loyalties to the victorious French. The chaplain Zwingli, still loyal to the Pope, left Glarus and moved to Einsiedeln, to the west of Glarus.

During this time, Zwingli had a change of heart. He decided the use of mercenaries was immoral. Further, he now believed unity among the Swiss was critical for the future of his people. His writings of the time attacked the use of mercenaries. He stayed in Einsiedeln two years and ended his participation in politics, focusing on his religious activities. He studied both Greek and Hebrew and acquired a large library. Zwingli proved a prolific letter writer; he exchanged letters with various Swiss humanists. He found the writings of Desiderius Erasmus of interest to him. Erasmus visited Basel twice in 1514 and 1516; Zwingli was able to meet the famous man. It is believed Erasmus influenced Zwingli to become more of a pacifist and to concentrate on preaching, becoming well-known for both his preaching and writings.

The Great Minister in Zurich - Public Domain

There were four great Protestant churches in Zurich. One was the Grossmunster (Great Minister). A post became vacant in 1518. A group of canons, administering this particular church, were impressed by Zwingli’s growing reputation. It turned out some of the canons were also in favor of Erasmus, whose influence on Zwingli made him more attractive. Politically, many Zurich residents had turned against both the French and mercenaries. Thus, Zwingli was both available and attractive for his influences, skills and experience. He was offered and accepted the position of priest in Zurich in December 1518.

Early Ministry in Zurich 1519 – 1522

Wasting little time, Zwingli delivered his first sermon on January 1, 1519. In Catholic churches, the priest usually gives a sermon based on that Sunday’s Gospel reading. Father Zwingli changed this approach. He read from part of the Gospel of Matthew and gave his opinion of the important points. Subsequent Sundays found him following the same plan. Finished this Gospel, he continued with other New Testament works and then moved to the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament). He encouraged his congregation members to improve their morals and religious understanding, both in line with Erasmus’s own beliefs. Zwingli was the first to introduce congregational singing.

He began to modify his approach. Whether he learned from Erasmus or, as some believed, Martin Luther, is not clear. What is known is that Zwingli began to attack, by name, particular individuals he believed to be lazy and not living as directed by their vows. One of his concerns was the blurring of facts and fictions (legends) about various saints; Zwingli began to call for the ending of venerating these people. Additionally, he criticized the damning of unbaptized children. He questioned the effectiveness of excommunication (the formal expulsion of a member of a Christian community) and began to speak against tithing (a tax paid to the Church for various reasons).

His speaking against the congregants’ paying for many services caused one of his electors to speak against him. The money from tithing paid for many of the costs associated with the staff and needs of churches. When asked, Zwingli stated that his evolving decisions were all based on Scripture, on the Holy Bible itself.

Just at the end of January, 1519, one Bernhardin Sanson (probably a Franciscan priest) arrived at Zurich. He was interested in gathering money for the building of Saint Peter’s Church in Rome. He offered the people of Zurich an indulgence; those who contributed money to the building project would receive reductions of punishment for sins they had already confessed. Not surprisingly, many of Zwingli’s congregants came to him with questions about this practice. He quickly answered they had not been correctly taught about indulgences and were being tricked. Partly due to Zwingli’s answers, the Zurich council refused entry into the city to Sanson.

That same year, plague strongly struck Zurich. Some 25% of the population died. Many people fled the city but Zwingli stayed, continuing to perform his priestly duties. He caught the disease and almost died. Most likely his prestige increased among Zurich’s population for staying and assisting the people. Indeed, in 1521, one position for canon became vacant. He was elected and thereby also became a citizen of Zurich.

Portents of Trouble

Lent is traditionally a time of fasting prior to the feast of Easter. On March 9 of 1522, Zwingli and several other people broke the rule of fasting by eating some sausages during Mass. Probably many people were shocked, but Zwingli defended his actions. He stated there was absolutely no clear rule on food in the Bible, so not obeying the non-rule was not sinful. This event was later called “The Affair of the Sausages;” many consider it to be the beginning of the Protestant Reformation in Switzerland. Not surprisingly, the Catholic hierarchy were not pleased. Zurich’s council did speak against what they believed was a violation of fasting, but they asked the diocesan religious authorities to provide clear information on the issue. The bishop later scolded the members of the Grossmunster and the city council. He restated the usual thinking.

Father Zwingli, in cooperation with other humanists, did request that the bishop end required clerical celibacy. The petition was quickly printed and widely spread among the now widely literate public. It turns out Zwingli had secretly married Anna Reinhart, a widow. They celebrated in 1524 with a public wedding; eventually they had four children.

The bishop replied by informing the city council to follow the previous tradition. About this time, other Swiss priests began to support Zwingli’s positions. He issued his first “position paper” on faith, titled Apologeticus Archeteles (The First and Last Word). Zwingli had been accused of causing unrest and of heresy. In his paper, he strongly denied both charges. Further, he stated that because of the endemic corruption in Church leaders, they had no right to judge such matters. As time passed, more citizens of Zurich began to turn against the local bishop and his traditional views.

Dissent grew so much that the Swiss Diet, the legislative and executive council of the Swiss Confederacy became involved. Each canton sent one or more delegates to the Diet. The cantons themselves were quite independent, so the Diet had limited power. At the end of 1522, Diet delegates voted to forbid any new religious teachings. The unhappy Zurich council decided to take action. They held a meeting in early 1523, inviting city and area clergy to prevent their ideas. The bishop was also invited and sent a representative.

At the meeting, Ulrich Zwingli presented his position in another paper. The bishop’s representative was surprised as he had not expected any sort of academic discussion. He was also forbidden by the council to speak about theology before ill-educated laymen. The council decided that Zwingli could continue with his ideas. Other preachers should base their talks only on sacred Scripture.

A close friend of Zwingli was the Catholic priest Leo Jud. In 1523, he began to speak for removing statues of saints from religious buildings. Many people agreed and took part in demonstrations and statue smashing activities. Once again, the Zurich city council became involved to make decisions about religious images. They included a discussion of the Mass itself, traditionally believed to be a “true sacrifice.” Zwingli had started to view it as some sort of meal of commemoration. Again, the bishop was invited. However, invitations were extended to lay people (non-religious), members of other dioceses and a university. Some nine hundred people attended, but neither the bishop nor his representative.

One group of young men who attended insisted on faster change. They believed infant baptism should be ended, replaced by baptism of adults. One issue quickly arrived which threatened to confuse the whole matter: who ultimately had authority over such a meeting – the city council or the Church?

One attending member was Konrad Schmid, a fellow priest and admirer of Zwingli. He suggested that statues were valued by some, so clergy should not address this subject. Schmid believed people’s opinions would eventually change. Later that year the council supported his position. Zwingli produced a work on the duties of a minister; the council adopted it and sent it to clergy members.

The Zurich council remained very involved in religious matters. In late 1523, they decided to set a deadline for the ending of both Mass and religious images. Zwingli gave his opinion against an abrupt, all-encompassing end. Council members decided to remove images inside Zurich, but to allow congregations in rural areas to vote whether to keep or remove images. Any decision about the Mass was delayed.

Reform changes continued. Clergy no longer wore traditional robes in processions. Many people no longer carried palms on Palm Sunday. The bishop of Constance attempted to end these decisions but, with Zwingli’s opinions, the council voted to end all connections between the city and the Church diocese. Some people began to participate less in religious activities, such as the Mass. In reaction, some priests reduced or even ended their celebrating the Mass. A great deal of confusion on the subject was apparent. In reaction, Zwingli decided to provide a German language liturgy on the topic of communion. Just before Easter, Zwingli and other priests requested the council to end the requirements for Mass and to introduce the new style of worship.

Zwingli himself simplified the service. No more gold or silver chalices. He used wooden plates and cups. People sat at tables, heightening the idea of a meal. No singing or music was included. The sermon became the center of the service. About the same time, the ever-busy Zurich council, again with Zwingli’s influence, decided to offer pensions to priests and nuns, ending their religious service. Church properties were taken over by the state. Zwingli received permission to open a school to retrain Zurich’s clergy.

Some reformers turned against Ulrich Zwingli. They believed he worked too closely with the council and rejected the idea of a civil government having control over the faithful. They wanted an independent religious organization. In 1524, the council decreed that all newborn babies should be baptized. Early the next year, the council members announced anyone refusing to baptize their infants must leave Zurich. Some citizens ignored this decision and began to baptize adults; this was the beginning of the Anabaptist movement. This question of the age of baptism became a contentious issue. In November of that year another meeting took place but each side refused to budge.

The council members decided no person could rebaptize anyone else, under penalty of death. It is believed Zwingli quietly approved. One Felix Manz had left Zurich, but returned and continued to baptize adults. He was arrested, tried and executed by drowning. Three more of the Anabaptists were executed. The rest fled to different locations or were forced out of the city .

People in five other cantons allied themselves to protest Zwingli’s changes. They contacted rivals of Martin Luther and a debate was arranged between Johann Eck (who previously debated Luther) and Zwingli. Many details were left undecided, so Zwingli decided not to attend. Nevertheless, delegates from all cantons travelled to Basel. The Catholic part was opposed by the reformers, led by one of Zwingli’s friends, Johannes Oecolampadius. The Diet heard both sides and decided against Zwingli. His writings were ordered to no longer be distributed and he himself was banned. Despite the personal ban, the Reformation teachings and practices continued to spread and be accepted in other areas of Switzerland.

Zwingli had the idea to create an alliance of cities with Reformed Christians were in charge. The city of Bern joined, as did Basel, St. Gallen, Biel, Schaffhausen and Mulhausen. Five of the cantons remained staunchly Catholic. They allied with Ferdinand of Austria, ruler of Austria in place of his older brother Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1529. Shortly after, a Reformed preacher was captured and executed in Schwyz. Zwingli reacted strongly and wrote a justification for war against the Catholic states. Zurich raised an army of 30,000 men. Ferdinand changed his mind and abandoned the Catholic states, who could raise a smaller force of only 9,000 men. The forces met at Kappel, but agreed to an armistice. There was general disagreement as to proposed terms. The Catholic states did end their link to Austria. This was known as the First Kappel War. Zwingli failed to reach his goal of freedom for Reform preachers to teach throughout Switzerland, but he himself continued to teach.

One of Martin Luther’s colleagues was Andreas Karlstadt, holder of a Master’s Degree and Doctorate in Theology. He wrote pamphlets about the Mass (also called “The Lord’s Supper) I which he stated the Christ was not actually present in the Eucharist (the host); the priest had not power to transform the bread into Christ. Zwingli read Karlstadt’s pamphlets, liked them and approved them. Luther, in his turn, rejected Karlstadt’s interpretation and thought Zwingli was merely Karlstadt’s follower. Zwingli then wrote his own papers stating that as Christ had ascended into Heaven, he could not also be in countless hosts.

Luther continued the debate. Philip of Hesse, a wealthy and powerful Landgrave (Count) tried to bring the men together to discuss these issues. He suggested they meet at Marburg. Both agreed and the Marburg Colloquy took place, with other theologians also attending. Fifteen Marburg Articles were published after the meeting. Luther and Zwingli agreed to fourteen. They expressed disagreement on the fifteenth, the presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Luther said Christ was present, while Zwingli disagreed. Zwingli highly regarded Luther. It is believed Zwingli read many of Luther’s writings. He wept as they parted, since they could not come to agreement. For his part, Luther regarded Zwingli and his followers as non-Christians.

Needing a strong backer, Zwingli attempted to rekindle an alliance with Philip of Hesse and they exchanged several letters. Philip’s superior, the Emperor Charles V, invited Protestants to the City of Augsburg in Germany. There, a Diet (formal meeting) was scheduled. The followers of Luther presented their teachings, as did also four Protestant cities. Zwingli prepared and presented his private “confession” of faith, the Fidei Ratio (Account of Faith), based largely on the traditional Apostles’ Creed.

In 1530 Philip established a new political League. Several cities were invited to join. Zwingli declined, stating his beliefs were against those of some cities. Philip took offense. Zwingli and some cities lost their possible protector.

The question of Reformists preaching in Catholic areas had not been settled. Several cities outright rejected any such Protestant attempts. Zwingli was all in favor. He called for armed attack against the rejecting cities. Surprisingly, in October of 1531, the opposing cities declared war on Zurich. An undersize, poorly equipped Zurich army of 3,500 men met an army twice their size at Kappel. The battle, lasting merely one hour, was a disaster for Zurich. Some 500 Zurich soldiers were casualties, among them Ulrich Zwingli. Luther commented Zwingli’s death was “…a judgement of God.” Even Erasmus wrote that Zwingli’s death was a good thing, “… the wonderful hand of God on high.”

The Murder of Ulrich Zwingli – Public Domain

For Ulrich Zwingli, increasingly the basis of a Christian faith was the Holy Bible. He did not completely reject other authorities, but the Bible was supreme. One point of disagreement with Catholics was their belief that the water of baptism could wash away sins; Zwingli labelled this belief superstition. Further, there was no “sacrifice” of the Christ during the Mass. There could not be, as the Christ had made that one-time sacrifice long ago. Zwingli well understood the influences in Christianity of Judaism. He was firmly against the anti-Semitic teachings of Luther and some others, both Catholic and Protestant.

Back in Zurich, the council needed a successor to Zwingli. They chose Heinrich Bullinger in 1531. A lay scholar, Bullinger admired Zwingli and described him as both a martyr and a prophet. As the Protestant cities of Switzerland became stronger, Bullinger examined Zwingli’s reforms and brought many of them together, adopting most of Zwingli’s doctrinal points.

Legacy

There is no doubt Ulrich Zwingli was a complicated man. A scholar, influenced by humanism, he was known to possess a good sense of humor. He often discussed theological matters by using puns and small jokes. Believing all people would benefit from God’s word, he assisted poor people, calling for Christian communities also to aid them. He became a vegetarian and held there was no justification in the Bible for eating meat.

Ulrich Zwingli is considered the founder of Switzerland’s Reformed Churches, but also of the Reformed Church in the United States. This writer has visited several Reformed Churches in the United States and talked with members about their histories, doctrines (beliefs) and practices. There is a continuity of tradition from Ulrich Zwingli to many Pilgrim and Puritan (later called Congregationalists), Baptist and Reform Churches, whether they formally or informally agree. Their religious beliefs often translate to political participation; congregation members many times are quite conservative and in recent years they largely vote Republican. Lastly, Ulrich Zwingli is held as hugely important in the Reformation, often placed with both Martin Luther and John Calvin.